The lower belly pooch frustrates people at every fitness level. Even with regular exercise and healthy eating, this area often remains resistant to change. Beyond appearance, excess abdominal fat is linked to cardiovascular strain, disrupted sleep, and metabolic risk. At the same time, weakened core muscles can contribute to lower back and neck strain, discomfort during exercise, and poor posture.

Addressing a lower belly pooch requires more than endless abdominal workouts. Effective solutions combine proper core activation, breathing mechanics, targeted strength training, nutritional strategy, and lifestyle factors. In many cases, the visible bulge reflects deeper structural issues—such as diastasis recti, pelvic alignment, or poor activation of the transverse abdominis—that traditional crunches cannot correct.

This article outlines evidence-based strategies for reducing a lower belly pooch through functional exercise, breathing techniques, nutritional considerations, and hormonal awareness. You’ll learn how to strengthen deep core muscles, identify underlying contributors, and build sustainable habits that support long-term improvement.

What Causes a Lower Belly Pooch?

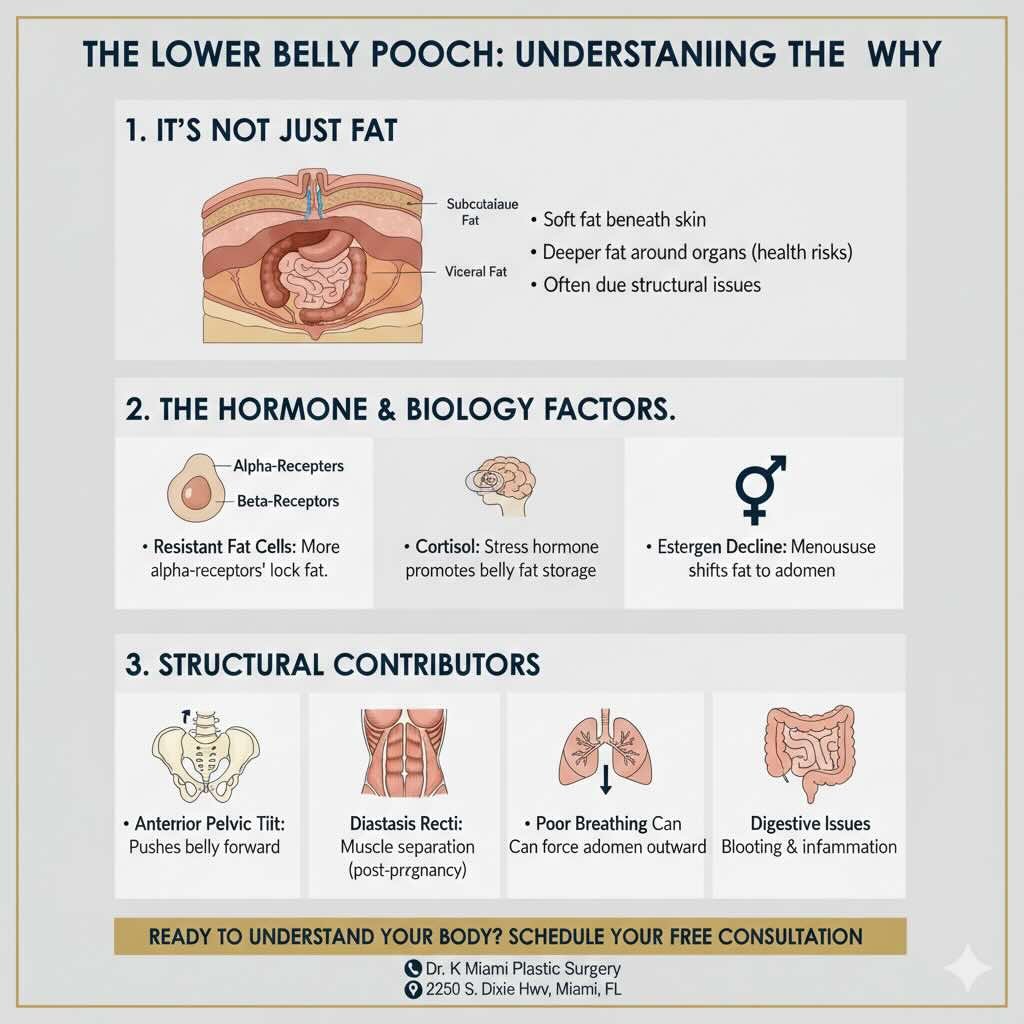

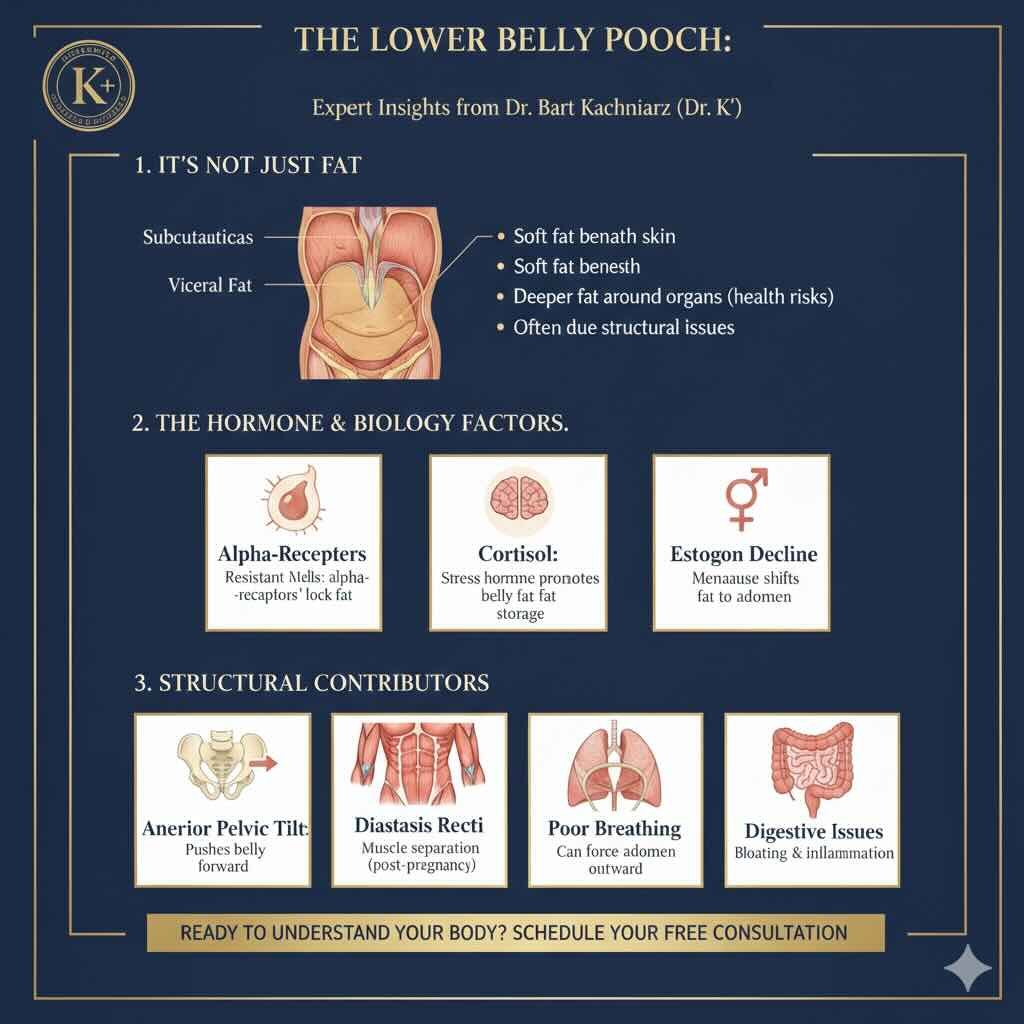

A lower belly pooch refers to a visible bulge below the navel and above the pubic bone. This region contains subcutaneous fat beneath the skin and, in some individuals, deeper visceral fat surrounding internal organs. The area typically appears rounded or protruding, feels soft to the touch, and does not fully flatten when the abdominal muscles are tensed.

Health Risks Associated With Lower Belly Fat

Lower abdominal fat carries health risks that extend beyond cosmetic concerns. Increased waist circumference is associated with higher rates of high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol levels, sleep apnea, heart disease, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, stroke, certain cancers, and increased overall mortality. Risk rises proportionally with waist measurement.

For women, a waist circumference above 35 inches signals elevated cardiometabolic risk. For men, the threshold is 40 inches. To measure accurately, stand upright and place a tape measure around your bare abdomen just above the hip bones. Keep the tape level and snug without compressing the skin. Relax fully, exhale naturally, and avoid pulling the abdomen inward during measurement.

Why Lower Belly Fat Is So Resistant

Fat stored in the lower abdomen is biologically resistant to breakdown. Fat cells in this region contain more alpha-adrenergic receptors, which inhibit fat release, and fewer beta receptors, which promote fat mobilization. As a result, the body tends to release fat from the limbs and upper body before the lower abdomen.

Hormonal changes further complicate fat loss. Declining estrogen during perimenopause and menopause, elevated cortisol from chronic stress, insulin resistance, and age-related reductions in growth hormone all favor central fat storage. These hormonal shifts make abdominal fat particularly resistant, even in individuals who maintain consistent exercise and nutrition habits.

Age-related muscle loss also plays a role. Without regular resistance training, adults gradually lose lean muscle mass, reducing metabolic efficiency and making fat accumulation more likely in the abdominal region.

Structural Factors Beyond Fat

A lower belly pooch is not always caused by fat alone. Several structural contributors can exaggerate abdominal protrusion.

Core Muscle Weakness

The transverse abdominis functions as a natural corset around the abdomen. When this deep muscle is weak or poorly activated, it fails to maintain intra-abdominal pressure, allowing the lower abdomen to push forward. The pelvic floor, deep abdominal muscles, and spinal stabilizers must work together to support the midsection. Traditional sit-ups and crunches often neglect these muscles and can worsen conditions like diastasis recti.

Posture and Pelvic Alignment

Anterior pelvic tilt is common, affecting approximately 75% of women and 85% of men without symptoms. When the pelvis rotates forward, it increases the lumbar curve and mechanically pushes the lower abdomen outward—regardless of body fat percentage. Tight hip and gluteal muscles can further reinforce this forward pelvic position.

Breathing Mechanics

Efficient diaphragmatic breathing depends on proper posture. A depressed sternum or chronically collapsed chest disrupts breathing mechanics, forcing abdominal contents outward during respiration. Ideally, the abdomen gently draws inward as air is exhaled. Poor breathing patterns can therefore contribute directly to a persistent lower belly bulge.

Diastasis Recti

Diastasis recti involves separation of the abdominal muscles, most commonly following pregnancy. Research suggests up to 60% of women experience abdominal separation in the first postpartum year, with roughly one-third continuing to have symptoms long-term. This separation allows internal contents to protrude forward, creating a visible bulge even in otherwise fit individuals.

Digestive Factors

Chronic bloating from constipation, incomplete bowel movements, or food sensitivities can increase lower abdominal distension. Pelvic floor dysfunction may also impair normal bowel function, compounding bloating and pressure in the lower abdomen.

When to See a Healthcare Professional

Persistent lower abdominal protrusion warrants medical evaluation when it does not respond to appropriate exercise and lifestyle changes. Seek prompt medical attention if you notice a firm or painful lump, bloating lasting longer than three weeks, or symptoms such as persistent diarrhea, vomiting, or blood in the stool.

A ventral hernia, unlike fat or muscle separation, presents as a localized bulge caused by tissue protruding through a weakened abdominal wall and typically requires surgical repair.

Common Myths About Lower Belly Fat

Clinical studies consistently show that targeted abdominal exercises strengthen muscles but do not reduce fat in a specific area. Spot reduction does not occur. Core training can improve posture and muscle tone, making the abdomen appear flatter, but fat loss requires a sustained calorie deficit affecting the entire body.

Extreme calorie restriction often leads to muscle loss, leaving the lower abdomen softer rather than firmer. Rapid weight loss also triggers metabolic adaptation, increasing the likelihood of fat regain. Detox teas and cleanses may temporarily reduce water weight through diuretic or laxative effects but do not result in true fat loss.

How to Get Rid of Lower Belly?

Effective core training focuses on deep stabilizing muscles rather than superficial movement patterns. These muscles engage continuously throughout daily activities such as standing, lifting, and walking.

Core Strengthening and Functional Exercise

The deep core includes the transverse abdominis, multifidus, pelvic floor, and diaphragm. These muscles function primarily as stabilizers. Exercises such as planks, bird dogs, and dead bugs challenge the core to resist movement while maintaining proper alignment. Beginners should aim for 20–30 second holds, gradually increasing duration as endurance improves.

The Vacuum Technique

The vacuum exercise specifically targets the transverse abdominis. Begin standing comfortably with hands on hips. Inhale deeply through the nose, then exhale slowly and completely through pursed lips. Once fully exhaled, draw the navel inward toward the spine and hold the contraction without breathing.

Start with three to five repetitions and gradually progress to ten to twelve. Proper activation can be confirmed by placing two fingers just inside the hip bones; you should feel firm engagement beneath the fingertips.

This technique can be performed lying down, seated, kneeling, or standing. Performing it on an empty stomach or at least two hours after eating improves effectiveness.

Breathing-Based Core Exercises

90–90 Breathing

Lie on your back with hips and knees bent at 90 degrees and feet supported on a chair or wall. Keep the lower back flat against the floor. Fully exhale through the mouth, allowing the ribcage to descend, then inhale slowly through the nose while maintaining abdominal tension. Perform two to three sets of five to eight breaths.

Prone Cobra Breathing

This exercise targets ribcage expansion and posture. Lie face-down with elbows under the shoulders. Gently lift the chest without arching the lower back. Fully exhale, then inhale slowly while expanding the upper ribs without straining the neck.

Full-Body Strength Training

Compound movements such as squats, deadlifts, and lunges build lean muscle while demanding core stability. Increased muscle mass raises daily calorie expenditure and supports long-term fat loss. Adults should aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly, along with resistance training at least twice per week.

Resistance bands add variable tension that challenges core control throughout movement. Targeted posterior hip stretching also helps reduce forward pelvic tilt and lower abdominal protrusion.

The Importance of Recovery

Muscle development and fat metabolism occur primarily during recovery—not during workouts themselves. Adequate rest between training sessions allows muscles to repair, hormones to stabilize, and metabolic processes that support fat loss to function optimally. Excessive exercise without sufficient recovery can slow progress rather than accelerate it.

Overtraining elevates cortisol levels, increases injury risk, and interferes with the body’s ability to mobilize stored fat. Balancing high-intensity workouts with scheduled rest days allows stress hormones to normalize and supports sustainable fat loss. Varying exercise routines also helps prevent burnout and improves long-term adherence.

Social support plays an important role in consistency. Exercising with a partner or participating in group fitness classes improves accountability and makes routine physical activity more enjoyable.

Nutrition Strategies for Reducing Lower Belly Fat

Reducing lower belly fat requires nutritional strategies that support both fat loss and digestive health. Whole-food choices, adequate protein and fiber intake, and attention to gut health directly influence abdominal fat storage and bloating.

Building a Strong Nutrition Foundation

Whole Foods:

Unprocessed foods provide essential nutrients without added sugars, sodium, and preservatives that promote inflammation and fat accumulation.

Protein:

Protein increases satiety hormones, preserves muscle during weight loss, and slightly raises metabolic rate. Studies show individuals with higher protein intake tend to carry less abdominal fat. Quality sources include lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, and whey protein.

Carbohydrate Quality:

Replacing refined carbohydrates with whole grains improves metabolic health. Individuals consuming higher amounts of whole grains have approximately 10% less visceral fat than those relying primarily on refined grains, even with similar calorie intake.

Fiber:

Soluble fiber slows digestion and promotes fullness. Research shows that every 10-gram increase in soluble fiber intake is associated with a 3.7% reduction in belly fat gain over five years. Fruits, vegetables, legumes, oats, and barley are strong sources.

Healthy Fats:

Omega-3 fatty acids from fatty fish may reduce visceral fat and liver fat. Aim for two to three servings weekly of salmon, sardines, mackerel, anchovies, or herring.

Foods to Limit:

Trans fats should be avoided entirely due to their association with inflammation and abdominal fat gain. Added sugars also directly correlate with increased belly fat and should be minimized.

Portion Awareness and Beverage Choices

Even nutrient-dense foods contribute to fat gain when consumed in excess. Practicing portion awareness—especially with calorie-dense foods—helps maintain a calorie balance. Caloric beverages are a common source of excess intake; replacing them with water or unsweetened options can significantly reduce daily calories without affecting satiety.

Digestive Health and Lower Abdominal Bloating

Food intolerances and digestive disturbances can create the appearance of a lower belly pooch through bloating and inflammation. Identifying trigger foods helps reduce abdominal distension.

Probiotics influence gut health and weight regulation, with certain Lactobacillus strains associated with modest reductions in abdominal fat. Natural sources include yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi. Because supplements are not FDA-regulated, consultation with a healthcare provider is advised before use.

Limiting excess sodium (ideally under 2,000 mg daily) and carbonated beverages can reduce fluid retention and gas-related abdominal distension.

Hydration and Mindful Eating

Consistent hydration supports metabolic efficiency and exercise performance. Even mild dehydration can impair fat metabolism. Mindful eating—without distractions—improves digestion and helps regulate portion size. Fullness signals can take up to 20 minutes to register, making slower eating particularly beneficial.

Strategic meal timing supports workouts and recovery. A light carbohydrate-protein snack 30–60 minutes before exercise supports energy levels, while post-workout meals emphasizing lean protein and vegetables aid muscle repair without digestive burden.

Setting Realistic Expectations

Lower belly fat reduction requires patience and consistency. Clothing fit often provides a more accurate indicator of progress than scale weight, especially as muscle mass increases. Many people notice changes in energy, strength, and overall body composition before lower abdominal changes become visible.

Safe, sustainable weight loss generally averages no more than two pounds per week. Habit formation typically takes 8–12 weeks, and meaningful abdominal changes often follow this timeline. Visible abdominal definition requires very low body-fat levels and is not a realistic or necessary goal for most individuals.

Lifestyle Factors That Influence Lower Belly Fat

Stress Management

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which promotes abdominal fat storage and insulin resistance. Evidence-based stress-reduction strategies include mindfulness meditation, yoga, breath-focused practices, and mindful eating.

Sleep Optimization

Sleep deprivation disrupts hunger hormones, increases cortisol, and promotes abdominal fat accumulation. Adults sleeping fewer than seven hours nightly show higher rates of central obesity. Menopause-related hormonal changes can further impair sleep and fat distribution.

Adults who consistently sleep fewer than seven hours per night show higher rates of central obesity compared to those who maintain seven to nine hours.

Effective sleep hygiene includes consistent sleep schedules, reduced evening screen exposure, a cool and dark sleep environment, limited alcohol intake, and morning light exposure.

When Lifestyle Changes Reach Their Limits

Diet and exercise cannot correct structural abdominal issues. Muscle separation, excess skin, and post-pregnancy changes often persist despite optimal lifestyle habits. Hormonal abdominal changes related to menopause or thyroid conditions may also resist conventional weight-loss strategies.

Once skin has stretched beyond its elastic capacity, it cannot retract naturally.

Temporary Appearance Solutions

Compression garments can temporarily smooth abdominal contours for special occasions. These should fit comfortably without restricting breathing or circulation and are best used as short-term confidence tools.

Advanced Body Contouring Solutions

When comprehensive lifestyle strategies fail to resolve lower belly concerns, medical interventions can address underlying structural issues. Dr. Bart Kachniarz, a Harvard- and Johns Hopkins-trained plastic surgeon, specializes in advanced solutions for persistent lower abdominal concerns.

Non-Surgical Body Contouring

Electromagnetic Muscle Stimulation:

High-intensity electromagnetic energy induces supramaximal muscle contractions, strengthening abdominal muscles and promoting localized fat metabolism. This option is particularly helpful for postpartum muscle weakness.

Cryolipolysis (Fat Freezing):

Controlled cooling destroys stubborn subcutaneous fat cells, which the body eliminates over time. This method does not tighten skin or repair muscle separation.

Radiofrequency Skin Tightening:

Radiofrequency energy stimulates collagen production, improving skin firmness in mild to moderate laxity without surgery.

Non-surgical treatments enhance—but do not replace—healthy lifestyle habits.

Surgical Options for Lower Belly Pooch

Tummy Tuck (Abdominoplasty)

A tummy tuck removes excess skin and fat while repairing weakened abdominal muscles. This procedure is particularly effective after pregnancy or significant weight loss. At Dr. K Miami Plastic Surgery, abdominoplasty is tailored to each patient’s anatomy for natural-appearing results.

Recovery typically requires 4–6 weeks, with full healing over several months.

Mini vs. Full Tummy Tuck

A mini tummy tuck targets the lower abdomen below the navel with a shorter incision and faster recovery (1–2 weeks).

A full tummy tuck addresses the entire abdominal wall, including muscle repair above the navel, and requires longer recovery.

Patients should not plan future pregnancies, as this can compromise results.

Liposuction

Liposuction removes localized fat deposits in patients with good skin elasticity. It does not address excess skin or muscle separation and works best for individuals near their ideal weight. Recovery typically takes 1–2 weeks.

Dr. K evaluates each patient individually to determine the most appropriate approach.

Ready to Address Your Lower Belly Pooch?

If diet and exercise haven’t produced the results you want, a personalized medical evaluation may help clarify your options. Dr. Bart Kachniarz offers complimentary consultations at his boutique Miami practice to assess your concerns and discuss appropriate treatment strategies.